When I started my writing career, I had visions of creating biographies of successful people for the children’s market. Checking in the school library where I taught kindergarten, I saw a gap in books about country music stars. But I did not know any country music stars. Frankly, in my naïveté, I didn’t know anything about interviewing and writing about anybody—famous or not. However, my vision did not dim.

When I started my writing career, I had visions of creating biographies of successful people for the children’s market. Checking in the school library where I taught kindergarten, I saw a gap in books about country music stars. But I did not know any country music stars. Frankly, in my naïveté, I didn’t know anything about interviewing and writing about anybody—famous or not. However, my vision did not dim.

In 1979, Grand Ole Opry and television’s “Hee Haw” star, Grandpa Jones and his wife, Ramona, had established a residence at Mountain View, Arkansas, only 40 miles from my hometown. From a brochure for their dinner theater in the folk music capital, I found a number—and I called—totally expecting a receptionist or secretary to answer the phone saying “Jones residence,” or perhaps, “Grandpa Jones Dinner Theater.” Instead, a man’s gruff voice picked up with, “Hello?” Just an abrupt ‘hello.’” I didn’t know what to say. I stammered, “Mr. Jones?” The voice answered: “Yes.” Hesitantly, I asked: “Grandpa Jones?” Again, the signature gravelly voice said, “Yes.” I explained why I called and asked if he would agree to talk to me. For the third time, he answered, “Yes.” We agreed on a time.

Totally inexperienced, I grabbed a notebook and pen—no tape recorder at that time—and I set out after school for my appointment at Mountain View. This famous music star sat with me on the porch of their dinner theatre and talked for two hours. In a frenzy, I wrote notes. Although my dream of writing biographies for children never happened, I did write several features about man I discovered was “Everybody’s Grandpa.”

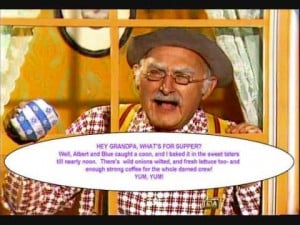

At the time of my interview, Louis Marshall Jones was a cast member on the homespun syndicated television show, “Hee Haw.” When the show’s audience yelled, “What’s for supper, Grandpa?” he peered over his tiny wire-rimmed spectacles and recited: “Cornbread, turnip greens, candied yams, butter beans, blackberry cobbler, and all things rare. The more you eat, the more to spare.” He gave no thought to reciting a menu of down-home cooking. After all, country vittles were ordinary to Grandpa Jones. He grew up around a dinner table laden with food grown in the family’s garden and seasoned with home butchered pork.

At the time of my interview, Louis Marshall Jones was a cast member on the homespun syndicated television show, “Hee Haw.” When the show’s audience yelled, “What’s for supper, Grandpa?” he peered over his tiny wire-rimmed spectacles and recited: “Cornbread, turnip greens, candied yams, butter beans, blackberry cobbler, and all things rare. The more you eat, the more to spare.” He gave no thought to reciting a menu of down-home cooking. After all, country vittles were ordinary to Grandpa Jones. He grew up around a dinner table laden with food grown in the family’s garden and seasoned with home butchered pork.

With his country persona, Jones was more akin to mountain folks. He spent his boyhood in Kentucky’s countryside, but he was a city boy during his youth. Born in Niagara, an incorporated community in Henderson County, Kentucky, he was the son of a share-cropper. His father turned factory worker and moved his family to the industrial towns of Kentucky and Ohio, looking for better financial times. Louis Marshall Jones spent his youth in a city. During their life on a farm, the elder Jones played fiddle and Mrs. Jones, a concertina. At the end of a workday, the Jones family gathered on their porch and played music against a backdrop of a summer evening’s twilight. The sounds of instruments mingling with voices in harmony dissipated the cares of their farming on the halves. No one thought about earning money playing music. The young Jones listened to the radio, especially the “National Barn Dance” out of Chicago. His strongest influences included old-time country music and gospel songs. The voice of country music legend Jimmy Rodgers inspired him to learn to yodel.

In Akron, Ohio, Jones attended high school and became a favorite performer in assemblies and school programs. He sang the old country songs and accompanied himself on his $12 guitar. During summers as a youth, he worked as a painter and a carpenter. The family’s landlady encouraged Jones to enter a local talent contest. Stage fright almost kept the 15-year-old frim trying for the prize. To his amazement, he won over other contestants and walked away with five $10 gold pieces jingling in his pocket. The prize money purchased his first quality Gibson guitar.

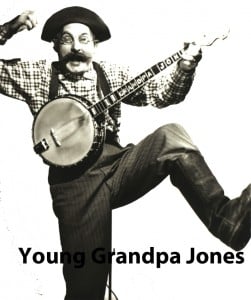

The morning after his win, Jones started a job on a local radio station, billed as “Marshall Jones, the young singer of old songs.” A career founded on a scared boy in an amateur contest led him through hundreds of performances at small-town courthouses, rural pie suppers, and local radio stations. Beginning in the 1920s, he attracted attention with his boisterous performing style, old-time drop-thumb flailing banjo playing, and powerful singing. By the 1940s, with hits like “Rattler” and “Mountain Dew,” he began receiving national attention. In 1946, he stepped onto the stage of the Grand Ole Opry. He loved entertaining people, but even with his successes, his parents continued to ask: “When do you intend to get a job?” He stored the idea of training for some other career in the back of his mind. Somehow, making people laugh and forget their woes through the strains of guitar, banjo, and song did not seem like work even to him. But the pace of one-night stands throughout the eastern states, plus appearances on local radio stations in between nightly shows, soon convinced Louis Marshall Jones that show business ranks among the hardest job roles.

At the age of 22, the hectic scheduling and lack of rest gave birth to his character, “Grandpa.” Sleepy from driving all night to get to a radio station for an early morning broadcast, Jones grumpily stood to perform. Emcee Bradley Kincaid said, “Get up to the microphone, you old grandpa.” Radio audiences wrote letters asking “Just how old is that fellow? He sounds like he’s 80!”

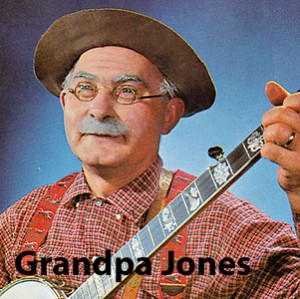

Capitalizing on his image—and his natural gritty voice— Jones added a false moustache and a few lines for wrinkles with a fine pencil. He adopted the name “Grandpa.” Kincaid presented him with a pair of 50-year-old boots. Over the months filled with miles on highways and country roads, Grandpa Jones completed his “look” with small round wire eye glasses, baggy pants held by suspenders crossing a cotton shirt, and an old felt hat. He literally aged into his character and eventually needed no make-up.

Capitalizing on his image—and his natural gritty voice— Jones added a false moustache and a few lines for wrinkles with a fine pencil. He adopted the name “Grandpa.” Kincaid presented him with a pair of 50-year-old boots. Over the months filled with miles on highways and country roads, Grandpa Jones completed his “look” with small round wire eye glasses, baggy pants held by suspenders crossing a cotton shirt, and an old felt hat. He literally aged into his character and eventually needed no make-up.

For over 60 years, the Grandpa Jones character strummed his guitar, plucked a banjo, and entertained audiences with country quips. Once on a Nashville Network show, Ralph Emory, host of the popular “Nashville Now,” said: “Grandpa, you are squinting. Can you really see through those little spectacles?”

With his usual quick wit, Grandpa answered: “Well, I ain’t a-looking around them.”

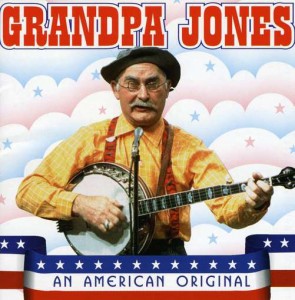

In 1969, “Hee Haw” propelled Grandpa Jones to a household name in America, although he had always been well known to country music fans for his banjo-picking and folksy style. Not a super-star by definition, Grandpa Jones had only two hit songs in his lifetime: “The All-American Boy” in 1959 and a cover of the Jimmie Rodgers’ signature song, “T For Texas” in 1962. Early on, he recorded with King Records, a powerhouse in country music at that time. Later, he signed with Monument, RCA Victor, and Decca Records, continuing to top the charts with songs such as like “Eight More Miles to Louisville.”

However, Grandpa Jones’ influence went beyond a string of hits. He almost single-handedly kept the banjo alive as a country music instrument during the 1930s and 1940s. He was known for the clawhammer style of playing, defined as a rhythmic strumming style as opposed to the picking style of bluegrass music. In addition to his own work and songs, he was an important associate and collaborator with country singer, Merle Travis.

Although tapings for “Hee Haw” and appearances on the Grand Ole Opry kept Grandpa Jones on the road about six months out of the year, he and Ramona made their residence in Arkansas for a period of time in the 1980s and 1990s. The unspoiled mountains and simplicity of lifestyle pulled deep at the core of their country roots. Ramona established the Grandpa Jones Family Dinner Theater on the highway that led to the Ozark Folk Center. Memorabilia from a long musical career filled one wall of the rustic log theater; his most cherished was a plaque inducting him into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1978. China plates, gifts from show business friends such as Roy Rogers and Dale Evans, Barbara Mandrell, and Tennessee Ernie Ford, covered a wall behind the country-styled buffet.

Although tapings for “Hee Haw” and appearances on the Grand Ole Opry kept Grandpa Jones on the road about six months out of the year, he and Ramona made their residence in Arkansas for a period of time in the 1980s and 1990s. The unspoiled mountains and simplicity of lifestyle pulled deep at the core of their country roots. Ramona established the Grandpa Jones Family Dinner Theater on the highway that led to the Ozark Folk Center. Memorabilia from a long musical career filled one wall of the rustic log theater; his most cherished was a plaque inducting him into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1978. China plates, gifts from show business friends such as Roy Rogers and Dale Evans, Barbara Mandrell, and Tennessee Ernie Ford, covered a wall behind the country-styled buffet.

Guests for dinner sat at tables covered with checkered tablecloths. In Ozarks fashion of “…making do with what you have,” various cane bottom chairs, wooden benches and a settee converted from an old bedstead, made seating arrangements. The gong of a dinner bell, followed by a simple blessing in song by the Jones family, marked the time to serve dinner. Ample servings on mismatched china plates were characteristic of the Ozarks lifestyle when families had little time or money for frills, but plenty of warmth and generosity for dinner guests.

Grandpa and Ramona Jones fit into Mountain View, located in north central Arkansas. They were impressed with the town’s dedication to preserving old-time country music. In Mountain View, away from the bustle of Nashville, they were regular neighbors and friends to the community. The family performed regularly at the Grandpa Jones Dinner Theater, and Grandpa joined them onstage whenever he was in town. He and Ramona deserve recognition for their contributions to country music, but also for their influence and support in making Arkansas known for its untainted beauty and cultural heritage. Grandpa’s concern for natural resources, both in people and the land, are summed up in a commercial aired on Arkansas radio in which an audience shouted: “What’s for supper, Grandpa?” And he flatly replied: “Nothin’ if we don’t stop wastin’ our nation’s resources!”

On January 3, 1998, Grandpa Jones suffered a stroke after performing his last set at the Grand Ole Opry. Exiting backstage, some person asked him for an autograph. According to his peer, Country Music Hall of Famer Charlie Louvin, Grandpa Jones said: “It looks like I’ve hit a snag,” his last attempt to be funny. He died on February 19, 1998. Louis Marshall Jones was 84; his character, Grandpa Jones was 62.

His memory and his music live on. Each year, The Ozark Folk Center, an Arkansas State Park in Mountain View, features a tribute to Grandpa Jones, which includes performances by Ramona Jones and family. The event for 2015 happens September 3-5.

Grandpa Jones was my first celebrity interview among internationally-known music artists—but not my last. I will always remember his generosity in time and words on that spring afternoon. His fellow country music stars call him a legend; his children call him “Daddy.” But Mrs. Jones and his friends and fans around the world, still call him “Everybody’s Grandpa.” And so do I.

Leave a Reply