Propane —a wonderful servant, and a dangerous foe. That’s why so much effort has been invested by the industry to try and keep LP the safe-serving friend that we RVers need. But sometimes those safety built-ins can create problems when they don’t work as designed. We’ll talk about the propane supply and LP cylinders and lines, what can go wrong—and how to fix it.

Propane —a wonderful servant, and a dangerous foe. That’s why so much effort has been invested by the industry to try and keep LP the safe-serving friend that we RVers need. But sometimes those safety built-ins can create problems when they don’t work as designed. We’ll talk about the propane supply and LP cylinders and lines, what can go wrong—and how to fix it.

Motorhome owners can probably nod off here; we’re talking to folks who have removable propane storage systems. While many RVers use the word, “tank,” to universally describe that container your rig draws propane from, there is a technical difference. Propane tanks are permanently mounted devices found on motorhomes. If you have a non-motorized RV, your propane is stored in a container that you, the owner, remove from the rig to get it refilled. These are propane cylinders.

We mark the difference because different design standards and regulations apply to these two different storage devices. Propane cylinders can also be referred to as DOT cylinders, the acronym standing for the Department of Transportation, which sets the standards for these containers.

Changes Required

In 2001, new codes for LP cylinder valves were rolled out, and most states have adopted them. That means that most states require your cylinder to be equipped with an OPD, or “overfill protection device.” You’ll know if you have one by the distinctive three-cornered shut-off valve. OPD valves are based on the theory that cylinders should not be filled beyond 80 percent of their rated capacity. The extra 20 percent allows for safe expansion of LP that might occur, for example, if you filled your container in a cold climate, and then immediately headed somewhere hot. The OPD valve would provide a safety margin for heat-caused expansion of the gas. In practice, not all OPD valves cut off the flow of LP at the 80 percent mark, or so say some LP filling station operators.

Inside of a cylinder equipped with an OPD valve is a small float that is pushed up as the level of LP rises in the cylinder. When the 80 percent level is reached, bingo! The float closes off the valve, stopping the inward flow of LP. But there can be a problem. You might hook up your freshly filled cylinder and be unable to get your gas to flow out. Some blame this on a “hung up” OPD float and recommend inverting the LP cylinder to solve the problem. DON’T! While it’s not likely to happen, you could conceivably get liquid propane into your gas line, rather than the gaseous form of LP. Liquid propane in a line is a fire or explosion hazard waiting to happen.

If you get a “hung up” LP cylinder, there are a couple of things to do. First, close the cylinder service valve and disconnect the gas line fitting. Reconnect the fitting and SLOWLY open the gas service valve, as in “barely crack the thing, then slowly turn it wide open.” Why? We’ll come to that in a minute. If it still doesn’t help, close the service valve, disconnect the gas connection, and locate a solid surface, like a smooth concrete walkway or solid earth. Make sure there aren’t any sharp objects like pointy rocks in the way. Grasping the cylinder by the safety collar up topside, give the cylinder a controlled drop onto the hard surface a couple of times. This often releases the “hang up,” and you’ll be good to go.

Pigtail Problems

Now, about that problem that you may have resolved by simply opening the valve slowly: that’s potentially an issue with your “pigtail.”

The assembly that connects your propane cylinder to the LP pressure regulator is often called a pigtail. That’s a throwback to the days when those assemblies were primarily a brass fitting connected to a coil of copper line. To allow safe expansion and contraction, and to reduce the chances of breakage due to vibration, the copper lines were coiled, resembling a pig’s tail. In the late 1970s, fire codes changed and mandated pigtails be made from rubber (later thermoplastic) tubing. Even then, the actual fitting to the cylinder valve was a left-hand thread fitting that screwed into the inside of the LP service valve, known as a POL valve. Why POL? Ah, an acronym for the company that originally developed them, Prest-O-Lite.

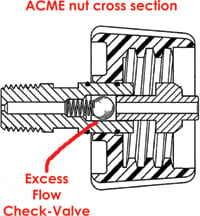

But when the new OPD valve became required, a new fitting was recommended, called ACME. No acronym here, and as far as we know, no relation to the company that supplied Wile E. Coyote all his stuff to go after the roadrunner. ACME nuts are plastic, right-hand threaded fittings that go over the outside threads on an OPD valve. They should be tightened by hand to prevent damage, and are easy to use.

ACME fittings are equipped with two safety protocols. First, they have a heat sensitive thermal bushing that if overheated, shuts down the flow of gas. Great for barbeque grills. Second, there’s an excess flow check valve. When the flow of gas is first allowed through the ACME fitting, the check valve closes, allowing just a small amount of gas through the fitting. This gas pressure builds up in the lines on the far side of the ACME fitting, and provided there aren’t any major leaks or broken lines, pressure builds up in the line, backing up against the check valve. When that happens, the check valves open fully to allow the maximum flow of gas.

Take Your Time It’s been found that if you open the cylinder service valve too quickly, the check valve will sometimes hang up and not allow the free flow of LP. Hence, the recommendation to close the valve, disconnect the fitting, reconnect, then slowly open the valve. Why disconnect the fitting? If you get a spurt of gas when you disconnect the fitting, you’ll know two things: First, that gas is actually getting through the cylinder service valve, and that you also had completely installed and tightened the ACME fitting.

It’s been found that if you open the cylinder service valve too quickly, the check valve will sometimes hang up and not allow the free flow of LP. Hence, the recommendation to close the valve, disconnect the fitting, reconnect, then slowly open the valve. Why disconnect the fitting? If you get a spurt of gas when you disconnect the fitting, you’ll know two things: First, that gas is actually getting through the cylinder service valve, and that you also had completely installed and tightened the ACME fitting.

The latter point is because there’s yet another safety feature in the new OPD valves. This safety prevents any gas from flowing out from the cylinder unless there is a completely installed fitting on the valve. This ensures you have a good seal between the fitting and the valve to prevent leaks, and also precludes the possibility of thermal injury. How’s that? Imagine your neighbor’s kid comes over, finds your filled LP cylinder just waiting to be hooked up, and opens the valve while the output is pointed at his face? ‘Nuf said.

Generally speaking, all these fittings, valves, and cylinders work in harmony and we can go merrily on our way. We recently had to replace an ACME pigtail when the check valve apparently decided to quit working. To diagnose the problem we tried reconnecting the ACME fitting a couple of times and banged the cylinder a couple of times, all to no avail. Then the “light came on.” We disconnected the second LP cylinder and moved the freshly filled cylinder to that “position.” Flow was immediately good from the fresh cylinder—the problem was the pigtail. Once it was replaced, our problem was solved.

One other problem you can prevent is the chance of clogging the pigtail check valve. Admittedly the likelihood of it taking place is slim, but here’s a tip. When you take your cylinder down to the station to have it refilled, always use the valve dust cap to keep bugs and crud out of the valve. It’s a far greater possibility that foreign material could get into the valve mouth if you left the cylinder disconnected and laying about in storage for a long period, but hey, why take the chances?

Got it all down? Like they say, now you’re cooking with gas!

Russ and Tiña De Maris are authors of RV Boondocking Basics—A Guide to Living Without Hookups, which covers a full range of dry camping topics. Visit icanrv.com for more information.

Leave a Reply